Death Valley National Park

The best time to visit Death Valley National Park is between mid-October and mid-April, that time of year when the daily high temperatures tend to remain below 100°F. On July 10, 1913, the high hit a world record 134°F... The park is open year round and modern well-maintained, air-conditioned vehicles shouldn't have any problems making a visit. It's when you open the door or window...

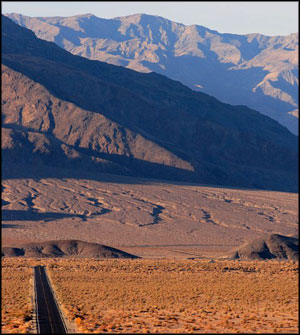

Death Valley National Park is immense, with more than three million acres of designated wilderness and hundreds of miles of back country roads. The landscape runs the gamut from salt pans to sand dunes to slot canyons to ragged mountain ridges and sharp peaks. Elevations vary from 282 feet below sea level (at Badwater Salt Flat) to 11,049 feet above sea level (at the summit of Telescope Peak in the Panamint Range). Panamint Valley and Death Valley are the two major valleys in the park and both are bounded by north-south trending mountain ranges. Plate tectonic action is pushing the mountains upward and allowing the valleys to drop.

There is evidence of Paleo-Indian presence in Death Valley dating back about 9,000 years. Archaeologists suspect the area was inhabited by a series of Native American cultures over the years, the first being the Nevares Spring People (hunter-gatherers who inhabited the area when there were still small lakes in the valleys and the climate was cooler), the most recent being the Timbisha who migrated up and down the elevations with the seasons about a thousand years ago. The name was given to the area by a group of gold seekers crossing the desert looking for a shortcut to the Northern California gold fields in 1849. Although only one person in their party died in the valley, they did have trouble finding a way out and ended up eating several of their oxen and abandoning their wagons in the process.

Over time a significant amount of mining has taken place in Death Valley and there are abandoned mine sites and ghost towns all across the property attesting to the temperament and the fortitude of those who would dig deep in hard rock for a few bucks...

The California Gold Rush of 1849 brought a lot of attention to the geological wonders of California and Death Valley was not left out. However, because of the primitive and inefficient technology coupled with the high cost of transporting their findings to civilization, it wasn't economically feasible to mine anything but the highest grade ores. One operation that was successful was the Harmony Borax Works, most famous for their "20-mule-team" wagons. But even that original mine was only worked for five years (1883-1888). Then a few big silver mines were dug in the early 1900's but they ran out of gas in the Panic of 1907. Prospectors keep looking, though, for copper, antimony, lead, tungsten and zinc. Large scale metal mining was pretty much out of the picture by 1915. That changed as technology advanced and new heavy equipment came into play. By the 1930's, open pit and strip mines started to be developed and by the 1960's, public outcry against the massive scarring of the landscape forced Congress to take action. That action was slow in coming, of course, but the Mining in the Parks Act of 1976 finally closed Death Valley to new mining claims, ended open pit mining and required the National Park Service to examine the validity of thousands of pre-1976 mining claims.

That stopped all mining in Death Valley National Monument for a while but some mining resumed in 1980 in a more limited way and under much stricter environmental standards. Death Valley National Monument became Death Valley National Park in 1994 and that legislation added 1.3 million acres to the park. Most of the remaining mines closed about that time but the Billie Mine, an underground borax operation near Furnace Creek, continued working until it closed in 2005. There are still a few outstanding mining patents and a few unpatented claims open but all are under increased scrutiny and none are being worked commercially.

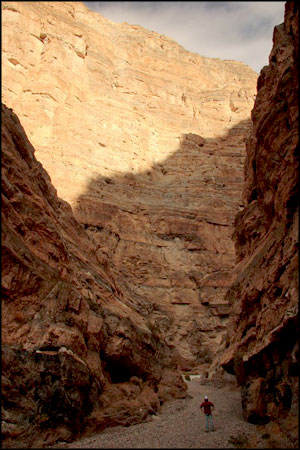

For a National Park as big as Death Valley, there are relatively few maintained trails. In most areas there's no real need for maintained trails as the desert makes hiking easy enough with virtually no thick brush anywhere. Most routes run across relatively easy country or up canyons or along ridges. In the canyons you might need to scale a few dry falls... in the desert it might get loose and rocky... the mountain slopes tend to be steep... and the best time to go hiking is October through April. For maybe half the year the temperatures (and sun exposure) in the lower elevations can be dangerous for hikers. The higher peaks stay relatively cool in the summer but can be snow-covered and icy in winter and spring. If you really need to go climbing in winter, better make sure you have proper winter clothing, an ice axe and good crampons. Wherever you go, you need to also realize that people need to drink more water here than anywhere else. The air is that dry... you might want to carry twice your normal ration of water and drink as you feel thirsty - don't save it for later. If you're feeling thirsty in Death Valley, you're getting dehydrated. There's also very few natural water sources in Death Valley and any water you come across out there needs to be treated or boiled before you drink it.

Palmer Canyon in Death Valley Wilderness

Some 3,102,456 acres (about 91%) of Death Valley National Park is designated wilderness. That means virtually all the countryside between the roads is protected from ever being turned into anything but wilderness. That wilderness is relatively easy to access because the boundaries are generally about 50 feet from the centerline of nearly every road. In all that space, it only takes a few minutes to get away from the road and experience the peace and solitude that envelopes most of Death Valley.

The primary reason for establishing Death Valley as a National Park was to preserve and protect the sheer volume and diversity of geological wonder exposed here. The rock ranges from 1.8 billion year old metamorphic rock in the Black Mountains to sand and salt deposited by the wind just yesterday. The location is on the western edge of the Basin and Range Province and that means the ground is full of fault lines. Small earthquakes are a regular phenomenon but the geologists all agree that the probability of a big earthquake isn't too far off in the future. Research indicates there are 61 geologic formations exposed within the boundaries of the park, some of them formed before life began on Planet Earth while others are filled with fossils of plants and animals long extinct.

There are nine campgrounds in the park. Except for the Furnace Creek Campground, the campgrounds in the lower elevations close for the summer. Most of the campgrounds at higher elevations are open year round but those higher in the mountains tend to close in the winter.

The Death Valley Visitor Center and Museum at Furnace Creek

The main visitor center is located in the Furnace Creek resort area on California Highway 190, about 30 miles from Death Valley Junction and 24 miles from Stovepipe Wells Village. The visitor center is open every day of the year. Summer hours: 9 am to 6 pm (mid-June through the first week in October); Winter hours: 8 am to 5 pm.

The Scotty's Castle Visitor Center is located in the northern part of Death Valley on Nevada State Route 267, about 53 miles from Furnace Creek, 45 miles from Stovepipe Wells Village and about 154 miles from Las Vegas, Nevada via US Highway 95.

National Park Service photos are marked "NPS"

Big map courtesy of the National Park Service